There’s a rhythm to life in my home neighbourhood of Kigoowa, and for many of my friends, it’s measured in alcohol. The clock starts ticking the moment they wake up. Most cannot go 12 hours without a drink of the strongest stuff, the kind that burns on the way down and quickly smothers the noise of the world. It’s easy to look at us, at the men I grew up with now staring into the bottom of a glass, and think, look at these guys, they’ve given up on themselves. And you’d be right.

I didn’t choose the bottle; my escape was a different kind of smoke. Not so long ago, I was heavily dependent on weed. It crept into my life promising clarity and courage, but it delivered laziness and a reckless haste in the decisions that mattered most. Just like my friends who had given up the will to find work, I was slowly giving up on the difficult work of building a life. We were a portrait of surrender.

But I've come to believe that judgment is too simple a frame for this picture. It's the easy answer that asks no hard questions. We must ask the hard questions. Is it truly a failure of individual will that drives a man to a drink before noon? Is it a fundamental flaw in our character that makes us reach for something to numb the sharp edges of the day?

Or is it a logical response to the world we are navigating? Is the drink, or the smoke, a rational anesthetic for a reality that has become too painful to feel? Perhaps the escape is not from our own minds, but from the quiet weight of shrinking opportunities, from the ghosts of traumas we were never taught to name, from the gnawing feeling that the game is rigged. Before we call it a weakness, we must consider that it might be a desperate form of shelter. We weren't just chasing a feeling; we were running from one. We had found a sanctuary, and we didn't yet realize its walls were a cage.

My cage was a comfortable one at first. In fact, it didn't feel like a cage at all; it felt like a key. I was 24 when I started smoking weed seriously, and it felt like I had unlocked a part of my own mind that had always been hidden. My meditation practice, which had been a struggle, suddenly deepened. With the help of the smoke, I could quiet the surface chatter and introspectively resolve my own psychic knots. The shyness that had followed me my whole life began to recede. The insecurity I harbored about my own intelligence, a feeling that I was somehow broken or dyslexic, dissolved. For the first time, I found the courage to write.

When a substance gives you tangible gifts like these—when it makes you more social, more focused, more courageous—it’s nearly impossible to see where the medicine ends and the poison begins. The line is invisible. You don't notice as the key that once opened doors slowly begins to lock them from the inside. The thing that helped you meditate becomes the thing you cannot meditate without. The music that sounded so vibrant now seems flat and lifeless. The desire to read, to write, to create, vanishes unless it is summoned by the smoke.

The key I thought I owned, soon owned me.

The turning point didn't come in a flash of insight during a meditation session. It came in a moment of pure, technological failure. I had smoked before a long, two-hour drive, a ritual to make the journey more interesting. As I settled into my seat and reached for my phone to put on some music or a podcast, I saw the black screen. The battery was dead.

For the next two hours, there was nothing. No music, no podcasts, no calls. There was only me, the hum of the engine, and the roaring silence of my own unmediated mind. It was the worst experience of my life. A wave of cold panic washed over me, followed by a frantic, desperate boredom. I was trapped with the one person I had been so expertly avoiding: myself. In that deafening silence, the truth finally had room to surface.

I didn't enjoy weed. I enjoyed how it made it possible to lose myself in something else. It wasn't a tool for engagement; it was a tool for escape. This terrifying thought led to a cascade of even more unsettling questions. Did I truly enjoy meditation? Did I love to read? Was I passionate about writing?

The answer echoed in the empty car. I did not know.

That chilling answer in the car—I did not know—began to haunt me. The question of my own authenticity started to bleed out into the world around me. I began to look at my society not as a collection of individuals making free choices, but as a landscape of engineered desires.

I started asking different questions. If we, as a culture, are naturally drawn to beauty, why is an entire industry invested in digitally perfecting and constantly reminding us of faces and bodies we must desire? If we genuinely love fried chicken and sweet drinks, why must billions of dollars be spent to splash their images on every billboard, every screen, every single day? Why is hip-hop music—once a genre of rebellion—now the ubiquitous, inescapable soundtrack to our consumption?

The answer became terrifyingly clear. It was my car ride, scaled up to the level of society. The weed was my focusing agent, the tool that allowed me to direct my attention away from the discomfort of my own mind. Advertising, shallow music, and the endless scroll of social media are now doing for society what the weed did for me: helping us all focus on anything but ourselves.

This isn’t just a philosophical idea; it is a biological process. My addiction wasn't simply a moral failing; it was my brain’s reward system being rewired. The joy of music or writing became chemically linked to a substance, and without it, the joy vanished. The modern world is now a grand-scale engine for this exact process. The infinite scroll of TikTok, the calculated cliffhanger at the end of a Netflix episode, the scientifically perfected “bliss point” of sugar and fat in our food—these are not just products. They are sophisticated tools for hijacking our dopamine systems. They ensure that unfiltered reality, and especially the silence of our own minds, becomes intolerably boring.

We are living in the age of the global anesthetic. The goal is no longer just to sell you a product, but to sell you a distraction from the single person you are forced to live with every moment of your life. A distracted, externally-focused person is the most profitable consumer of all. And so the real question is not, "Who is addicted?" but rather, "Who isn't?"

If we are living in a cage of global distraction, how do we begin to break out? The answer isn't a new app, a better self-help book, or another productivity hack. You cannot consume your way out of a problem caused by consumption. The answer is simpler and far more radical. The answer is refusal. The answer is rebellion.

I call it the Modern Sabbath. Not as a religious decree, but as a revolutionary act of self-preservation. It is the conscious decision to carve out a period of time—one afternoon, one day a week—and dedicate it to the radical act of doing nothing. This is not meditation with a guided voice in your ear. It is not listening to calming music. It is renunciation.

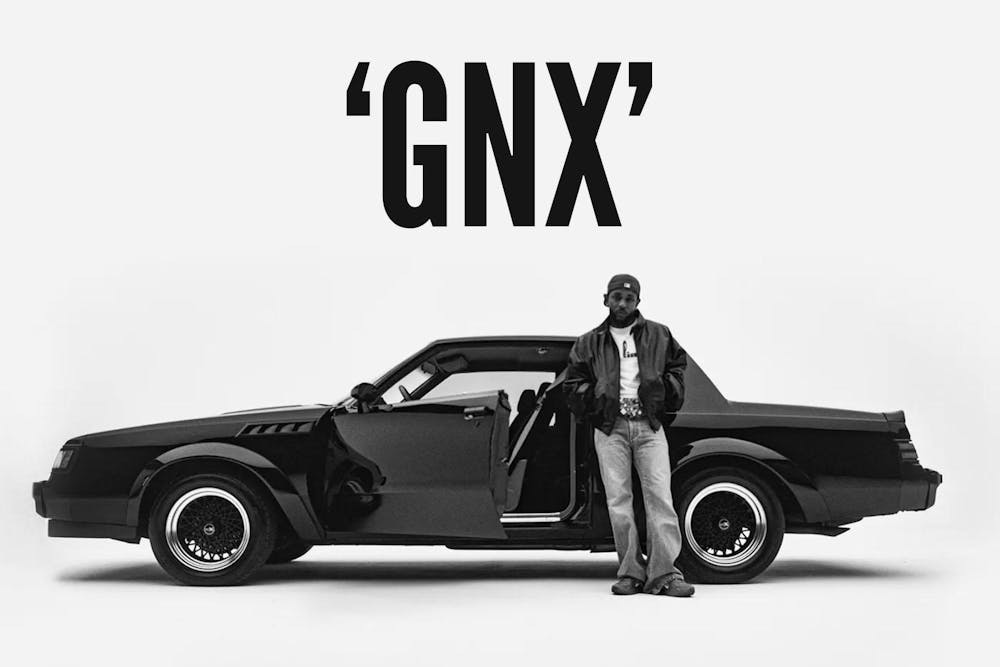

Turn this TV off, as Kendrick Lamar tells us. Put the phone in a drawer. No music, no podcasts, no books. The goal is not to consume better content; the goal is to stop consuming altogether, to starve the part of your brain that is addicted to external input.

I will not lie to you: it will be hell at first. Your mind, so accustomed to its anesthetic, will yell at you. It will scream with boredom. It will conjure a thousand anxieties and a million urgent, trivial tasks. It will beg for a fix. Your only task is to sit with it. Bear it. Don't fight the yelling, don't judge it, don't try to fix it. Just listen. You will learn that the noise is not infinite. You will learn that your mind’s rage is just a storm, and you are the quiet sky behind it.

But this rebellion is too hard to wage alone. We fell into these traps together, surrounded by people who offered us another drink or tagged us in another post. We must climb out together. The antidote to a community of distraction is a Community of Presence.

Seek out the friends with whom you can share a comfortable silence. Be the one who suggests a walk in the park with no phones allowed. Have conversations that aren't punctuated by the buzz and glow of notifications. We have to actively build the relationships that support our attention, not just participate in the ones that steal it. Taking back your attention is the personal battle. Finding those who will stand with you in the quiet is how you win the war.

What happens when you consistently sit through the storm? What is on the other side of the yelling?

It is not an empty void. It is a quiet clearing. Slowly, painstakingly, the desperate need for distraction begins to lose its power. The frantic energy subsides. And in that newfound quiet, a different voice begins to emerge. It’s a faint whisper at first, easily drowned out. It is your own.

This is the meeting you have been running from. You begin to learn your own, true appetites. You discover that, without the constant shouting of advertisements and influencers, you might not actually need the sugar and the oil. You learn that the endless stream of podcasts and expert advice was just another form of noise, preventing you from hearing your own counsel. You may even find, as I did, that you can enjoy music for what it is, not for what a substance makes it. You can write from a place of clarity, not chemical courage.

This self-knowledge becomes a shield. You gain the power of discernment. You can look at the vast, screaming menu of modern life—the shows, the foods, the outrage, the trends—and you can finally, confidently say, “No. That is not for me.”

And this is when the deepest realization of all dawns on you. You understand that your addiction was never the real problem. It was a symptom. It was a distress signal from a part of you that was being starved and ignored. It was a desperate attempt to silence your own inner turmoil because you had never been taught how to listen to it.

Perhaps addiction is your mind telling you that you have been listening to everyone except the one person you need to hear most: yourself.

Freedom, then, is not a battle won against a substance or a screen. It is a peace treaty signed with your own soul.

A peace treaty signed with your own soul is a profound victory. But a world that requires each person to fight a long and brutal war just to achieve that peace is a world that is still fundamentally at war with itself.

This raises the final, most important question. It’s the one we must ask ourselves after we have won our personal battles. Beyond our individual rebellions and our hard-won treaties, what does a society that vaccinates its citizens against this mass addiction look like? What if we didn't have to fight so hard just to hear ourselves think?

This isn't a nostalgic dream for a simpler past. It is a necessary vision for a more humane future.

What if our schools taught introspection with the same rigor they teach mathematics, equipping children not just with the ability to find answers online, but with the capacity to find them within? What if our cities were designed not only for commerce and traffic, but for consciousness—with more quiet parks, phone-free public squares, and libraries that served as sanctuaries for silence?

What if our economy valued deep focus over frantic productivity, and our workplaces encouraged true rest and disconnection as the prerequisites for creativity and innovation? And what if our art and our media sought not just to capture our attention for a fleeting moment, but to hold it gently, creating experiences that invite contemplation instead of just provoking a reaction?

The fight against addiction, in the end, is not just a grim struggle for personal recovery. It is a collective, creative project. It is the work of building a world that nurtures the inner life as much as it celebrates external achievement. It is the challenge to design a society that doesn't force us to choose between sanity and success.

It all starts with the quiet rebellion of one. Then another. Then a community. It starts by turning down the volume of the world so we can finally hear the whisper of our own voice. And then, together, we build a world where that voice has room to speak.

To be continued…

I am writing this as a follow-up to a previous post that I wrote about whether advertising works. Please read that next.