A Brief History of the Colonization of the Baganda

A good Muganda is a cunning one.

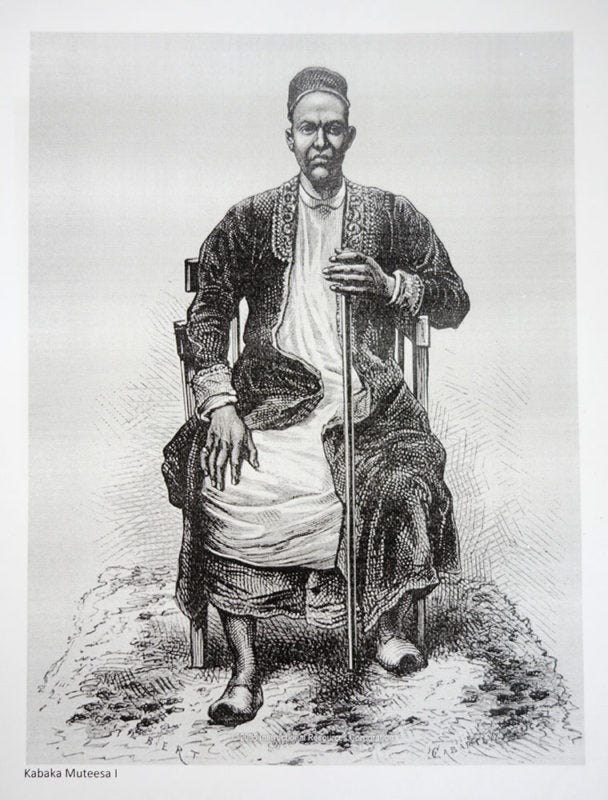

The most famous Muganda, Kabaka Muteesa I, invited the European missionaries so they could teach his brothers and sisters how to read and write. With his privilege as a Kabaka, Muteesa I had learned about the scribbling cultures of the people that lived in the womb of the sun and the people that lived in the tomb of the sun. The Arabs had already imported their ways into Buganda, and Muteesa worried that if the Baganda became Muslims, they might never be Baganda again.

In such a situation, a typical man would consider fighting the imported ways, calling them alien to the Baganda. But Kabaka Muteesa easily saw through this ill thought. He decided that instead of rejecting the Arabian ways, the Muganda shall not be reduced to a non-Muslim, but instead be given the choice to decide what kind of Muganda they preferred to become. So, the Kabaka also invited the Europeans.

When the Europeans saw what the Kabaka had done, they chose not to interpret it as a kindness to the Baganda, but as a weakness of their leader. So they conspired with the Arabs to abolish the gods of the Baganda. You see, they thought that the Baganda put their idea of God on a pedestal over all other ideas, just as they did. They invested heavily in converting some Baganda into Christians and some into Muslims, hoping that the Muganda would cease to exist entirely in favour of these new, god-made tribes.

But the Kabaka had already anticipated this trickery. The Kabakas before him had taught him that a good Muganda is a cunning one. Since a Muganda is first a Muganda before he is a Catholic or a Muslim, these forces were not able to mobilize sufficiently to get Baganda to fight against each other in the name of their new tribes.

So, the European looked to the periphery of Buganda. He wanted to find people who didn’t consider themselves Baganda enough, so that he could sow stories that would divide them against the Baganda. You see, Buganda is an organic nation that grows like algae. It was expanding west naturally into the Baruuli and then further and further, until every human being could be a Muganda.

Becoming a Muganda was simple. You could take a Kiganda name. You could start a clan from your family, join your father’s clan by birth, or join an existing clan by taking a name from it. To be a Muganda, you didn’t need to read a story in a book, slice up your genitalia, or have your parents pour water on your face when you were young. No initiation ritual was required. And while following such rituals would not deter one from becoming a Muganda, they were never a prerequisite. If you felt ready to be a Muganda, you became one. And if not, you could be a Musoga, a Munyoro, a Munyankole, a Mugisu, or any other. The Baganda wouldn’t mind, because those words were all simply synonyms for the English word “community.” One chose the community that made them comfortable, or even multiple communities, because they all knew that no community was perfect and no two people are equal. With this model of society, the Kabaka did not feel Buganda would be threatened by those who worshipped the moon or those who worshipped the cross.

What the Kabaka did not anticipate was this: unlike the Arabs who were all Muslims, the Christians were sometimes English, or French, or German. For those communities, the differences between them were emphasized more than the similarities. For one not to belong to their specific community was, for some unknown reason, a slight to those who belonged to that community. And so, these communities were always at war or in competition with each other. Because of these quarrels, the Christians were not one tribe either. Some were Catholic and others Anglican due to minor differences in the interpretations of their same book.

These internal divisions among the Europeans soon manifested among the Baganda, encouraging them to pay more attention to the differences between themselves. That is why, instead of being synonyms, Banyankole became a different people, Basoga became a different people, Banyoro, Bagisu, and others. The Europeans believed that to be European, one had to have that skin that feared the sun. Among them, the English believed one had to speak a certain dialect, preferably through one’s nose. So many nitty bits, here and there, divided the Europeans—details the Baganda would have simply called the uniqueness of each human.

When the politicians among the Europeans saw that division was novel to the Baganda, they used their experience to divide and combine them randomly, until they were made of combinations not self-sustainable enough to divide fully, and not similar enough to unite fully. But perhaps the best rabbit they ever pulled out of their hat was to convince them that they—the ones who have never been united, the same ones who had taught them how to be divided—knew that there was such a thing as unity, and that it is they who held the key.

It was not until one of them organised the most brutal war in their tribal history, one they arrogantly called a second world war, that the Baganda, the Acholi, the Banyankole, and all the others started to realize they had been duped. It was during that time that most movements for independence on the African continent thrived. But unfortunately, they underestimated how far the European was willing to go even with violence just to keep the divisions in place.

The problem is this: the Baganda confused the Christian God with the European God. Because the Europeans were Christians, the Baganda forgot that they were first Europeans. You see, the God of the European is Envy (Ebbuba), and such a God feeds only on competition. And competition inevitably becomes war.

The Baganda are now all confused, stuck in wars and petty competitions, not knowing that they have to look at the European’s actions—not their intentions or their thoughts, but their actions—to assess if they are worshipping the christian God they claim to be worshipping. Because until you actually look at the data and stop confusing European ways with Christian ways, you will stay divided. You will still think that Muganda doesn’t mean related, but that it means a tribe of people who are not Banyankole, Basoga, or any other synonym.